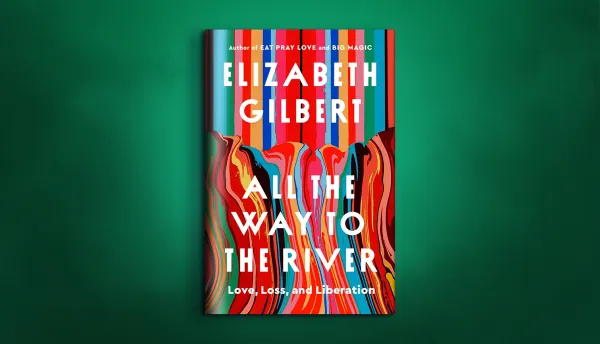

Elizabeth Gilbert has built a career out of telling stories of transformation. Eat, Pray, Love sold the dream of escape, reinvention, and finding beauty on the other side of heartbreak. But in her new memoir, All the Way to the River, Gilbert does something else entirely: she confesses that she once planned to murder her girlfriend (the person she divorced her husband she met in Bali to be with).

It wasn’t just a passing thought. She devised a method. She thought about swapping pills, slipping her partner sleeping tablets, and finishing the job with fentanyl patches. Rayya Elias was dying of cancer and had relapsed into addiction, and Gilbert, by her own account, was overwhelmed. But the plan was real. And she is telling us now, in plain words, that she considered killing the woman she loved.

The issue was that she wanted to live with Rayya during her last months and let it end as swiftly as it had started. All of this changed when Rayya decided to get treatment for her cancer, thus prolonging the time they had left. After the high of the initial rush of their relationship they began to have problems, and Elizabeth decided to kill her, and when that didn’t go according to plan, she left her dying partner. (Although she did say they reconciled before her death.)

This is where I find myself stuck—not in empathy, not in excuse, but in confrontation. We live in a culture that often wants to redeem confessions, to find the lesson, to see the darkness only as a stepping stone to light. But what if some darkness simply sits there, unable to be redeemed? What if the most important response is not forgiveness but recognition—that human beings, even the ones we admire, are capable of imagining atrocities against the people they claim to love?

My other problem with this book is that Rayya is dead, therefore we only have Elizabeth’s account of how things went down. There is something to be said about using dead people in your life who have other friends and families in your book in such a manner, because all of this was unprompted. At the end of the day, no one asked her to do this.

And maybe that is the only honest way to read this book. Not as a guide. Not as a lesson. But as an admission meant to break the illusion of safety we like to wrap around love and around our heroes. Gilbert’s confession doesn’t leave room for comfort. It leaves us with a question that lingers long after the page is turned: what do we do when the people who teach us about love reveal just how close they came to destroying it?

What do you think?